Two research teams, one from Switzerland and the other from Australia, have separately created nanodevices that can produce electricity from common physical processes, opening up new possibilities for battery-free, sustainable power. Both experiments, which were published this week in Nature Communications, show how mechanical pressure and evaporating seawater may be converted into useful energy through nanoscale engineering.

Using Saltwater To Generate Power

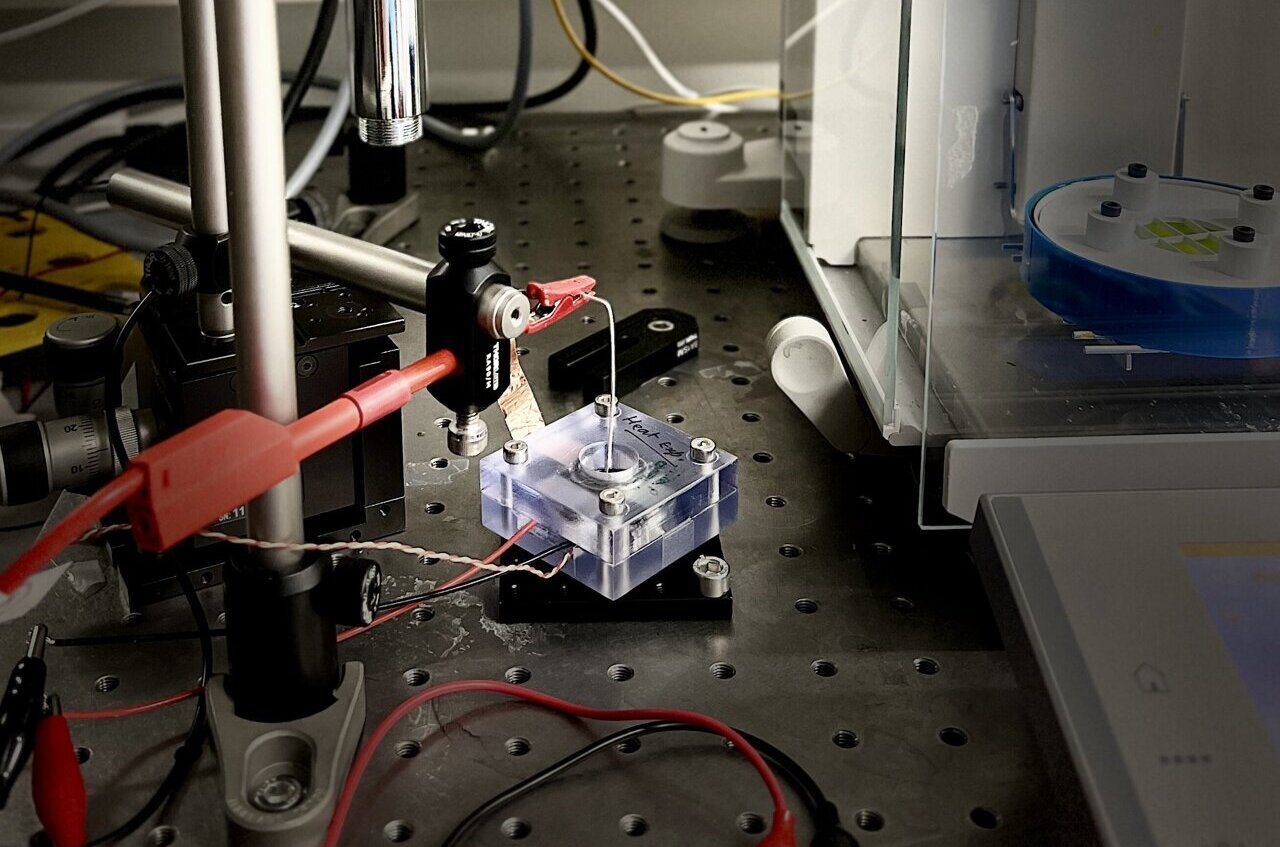

A group at the Laboratory of Nanoscience for Energy Technology at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), under the direction of Giulia Tagliabue, has constructed a hydrovoltaic device that uses evaporating saltwater to generate a continuous, independent electric current. Each process may be separately adjusted thanks to the system’s hexagonal array of silicon nanopillars with three separate layers: one for evaporation, one for ion transport, and one for electrical charge collection.

The main breakthrough is that light and heat do more than only accelerate evaporation. Heat intensifies the negative charges on the silicon semiconductor’s surface, while photons from the sun excite the semiconductor’s electrons. Ions in the seawater that is evaporating simultaneously move, forming charge separations that cause current to flow across a connected circuit. “Our work shows that due to this surface charge effect, the addition of solar light and heat can enhance energy production by a factor of 5,” Tagliabue stated. The apparatus attains a power density of 0.25 watts per square meter and an open-circuit voltage of 1 volt. Wherever there is water, heat, and sunlight, the researchers see it powering wearable technology, sensor networks without batteries, and internet-of-things applications.

A Car-Surviving Nylon That Continues To Produce Power

A different team from RMIT University in Melbourne, lead by Dr. Amgad Rezk and Distinguished Professor Leslie Yeo, has used electric fields and high-frequency sound vibrations to turn regular nylon-11 into a robust power-generating film. As the nylon hardens, the process reengineers it at the molecular level, arranging its molecules to generate a piezoelectric charge when it is tapped, squeezed, or bent.

The material is extremely resilient; even after being repeatedly run over by an automobile, it continued to produce energy and maintained steady performance throughout 20,000 compression cycles at 50 newtons. The researchers claim that its piezoelectric voltage coefficient is higher than that of any piezoelectric polymer that has been documented to far. The first author, Robert Komljenovic, a Ph.D. researcher at RMIT, stated, “You can fold them, stretch them, even run a car over them — and they keep making power.”

Moving Toward A Future Without Batteries

Both developments tackle a recurring issue in energy harvesting: converting lab-scale performance into systems that are reliable enough for practical use. While RMIT’s nylon films provide a nontoxic, recyclable, and biodegradable substitute for fluorinated piezoelectric polymers, the EPFL team’s oxide-coated nanopillars withstand deterioration in corrosive saltwater environments. While the EPFL group intends to test solar simulators to improve their gadget in real time, the RMIT team is currently looking for industry partners to scale up the technology for applications ranging from smart road surfaces to wearable electronics.